In

1976, an MIT graduate named Larry Rosenthal, who had

been attempting to lure various coin-op companies

to buy into his new Space Wars video

game prototype and his patented vector graphics display,

finally landed at Cinematronics, a company based at

El Cajon, CA and in the business of manufacturing

Pong variations. Rosenthal's demand

of a equal split of future Space Wars'

profits between himself and the manufacturer, as well

as the licensing of his Vectorbeam monitor rights,

were scoffed at by all companies in the business...all

except Cinematronics, then co-owned by Tom Stroud

and Jim Pierce, who decided to give it a shot.

Space Wars itself was based upon a game

which had been around for years, initially created

by MIT student Steve Russell (and his hacker buddies)

as a demostration of the capabilities of the old PDP-1

computer. Whether or not the "Space War"

game idea itself was actually copyrighted by Rosenthal

is not clear, but there have been murmurs that he

actually obtained the copyright of the game from Russell,

which would contradict the well-known rumor of the

game being public domain. What is known, however,

is that Rosenthal possesed the copyright to his vector

display, which he called the "Vectorbeam" monitor,

and which he licensed to Cinematronics for each Space

Wars game produced.

This new vector display was capable of rendering only

straight lines between points, no solid or rounded

shapes as in the normal raster displays, and even

though this limited the detail of the graphics to

some degree, the resolution was phenomenal, a bright

crisp contrast to the heavily pixelated games of the

time. To his credit, Rosenthal's use of the vector

display seems to have been proven as a major reason

behind the success of Space Wars, as

the first coin-operated video game called Computer

Space, designed by Atari founder Nolan Bushnell

and produced by Nutting Associates in 1972, had also

been based on Russell's "Space War"

game. In contrast to Rosenthal's Space Wars, Bushell's

Computer Space was a blocky, slow mess,

which was more frustrating to play than fun. Space

Wars, having the technological advantage of coming

five years after Computer Space, was

a smooth, fast and beautiful creation, with many options

to spice up the head-to-head spaceship battle. Players

could choose to make the center of the screen a "Black

Hole" which would suck the ships into its core and

destroy them. Or players could choose the opposite,

to have the center repel the ships with "negative

gravity." They could also choose to have an expanded

universe, in which the battle would continue outside

the screen, players using only their memory as a reference

to extrapolate shots and flightpath, intercepting

their opponent. A wonderful creation that quickly

impacted players across the country.

Space Wars became wildly popular in

arcades, rated by game operators as the top earner

of the year in 1978. Sales figures of the game are

estimated to be in the neighborhood of 30,000 units,

and given Rosenthal's deal with Cinematronics, it

is safe to assume that he quickly became a very wealthy

man, the profits of Space Wars netting

him what would appear to be an eight figure sum

(Do the math).

The video game business was, and always has been,

all about following the leader. If a game, a game

feature, or a specific technology became popular (a

word synonymous with profitable in the coin-op

world), it was certain to beget derivatives. Thus

began the fabled and meteoric rise of vector games

in the world of coin-operated amusement. And if the

folks at Cineamtronics had stopped the Space

Wars manufacturing line, and switched off

the loud equipment, a dull rumble could have been

heard, to the north, at the industry acropolis of

Atari.

Space Wars stayed atop the charts for

months to come (in fact it was still one of the top

ten games in 1980) but Rosenthal soon left Cinematronics

to start his own company which, like his display technology,

he also called Vectorbeam. Whether or not Pierce and

Stroud grew a dislike for the 50-50 profit split with

Rosenthal and pushed him out, refusing to repeat the

arrangement on his next game, or whether a different

situation occured, is unclear. The split off was definitely

not amicable, but either which way, Rosenthal used

the substantial revenue from Space Wars

to start Vectorbeam, which was solely dedicated to

producing coin-operated vector games (the only company

ever which can claim this).

Vectorbeam also had the right to produce Space

Wars, and they did, dropping the "s" and calling

it simply Space War, but with the exact

same features and gameplay of the original. Other

than Space War, Speed Freak, the unique

vector driving game, was the only real production

game that came from Vectorbeam as it existed under

Rosenthal. Speed Freak was the most

advanced driving game of its time, and it definitely

lived up to its name; your speed increases exponentially

as you hold down the throttle in fouth gear, giving

good players an amazing ride for a quarter. (The cars

which the passed the player's on the road were 3-D

and wireframed, a predecessor to the tanks which would

later be used in Battlezone by Atari).

Back at Cinematronics, immediately after Rosenthal

left in early 1978, Tim Skelly was hired as the sole

game designer, beginning work on Starhawk,

a first person shooting game. However, when Rosenthal

left to form Vectorbeam, he cleaned house, moving

all of his developing tools over to Vectorbeam and

taking the only copy of the instructions for programming

the CPU, which requiried Skelly to effectively start

development from scratch and reverse engineer Cinematronics'

own CPU board. The result was Starhawk

missing the AMOA show of 1978, an omission detrimental

to sales at the time. Starhawk, however,

made the show in London soon afterwards and was still

enough of a success to keep the doors open and, along

with the still popular Space Wars, kept

Cinematronics' workers employed.

Skelly pressed on and created Sundance,

a very unique game but one with numerous manufacturing

flaws. The phosphor coating on the inside of the game's

monitor was applied incorrectly, flaking off and causing

the monitor circuit boards to short out. Additionally,

the monitor circuitry itself was very fragile, as

they added a gray scale adapter to it, requiring lots

of cuts and jumper wires. This resulted in most Sundance

machines arriving at their distriubutors DOA , therein

immediately returned for a refund.

Dan Sunday, a designer at Vectorbeam along with Rosenthal,

had started the development of the game Tailgunner,

and also a primitive "rotating rings" game that would

later inspire the creation of Star Castle,

both to be released by Cinematronics after the buy-out.

Yes, that's right. Vectorbeam only lasted about one

year (from the fall of 1978 to the fall of 1979) and

then Rosenthal sold the factory and the Vectorbeam

technology rights to Cinematronics. He then took his

substantial wealth (even after the failure of Vectorbeam

he was still easily a millionaire) and left the game

business for good, never to be heard from again.

One mystery he may have left unanswered forever is

the game Scramble. Some say it was produced,

and others claim only a flyer and a mock-up cabinet

were ever produced. No Scramble has

ever been found, and nobody with a definite recollection

of ever seeing a Scramble has ever spoke

out. It may very well remain a mystery...

The game Barrier, manufactured just

after the Vectorbeam buyout by Cinematronics, is also

an interesting story. Barrier was a

game designed at Cinematronics as an excercise for

newly-hired programmer Rob Patton, and was initially

named Blitz. Jim Pierce, co-owner of

Cinematronics, came up with the gameplay idea, which

was curiously identical to the handheld Mattel

football electronic game which was very popular at

the time. As Skelly remembers, "To make Jim happy,

we put it out on test. It did very poorly, to put

it nicely, and we stuffed it in the closet."

Bill Cravens, President of Vectorbeam, visited Cinematronics

before the buyout, looking for something his company

could build and and sell quickly. "Cinematronics sold

him Blitz," Skelly says. "And we all

laughed our asses off."

However, the laughter died abruptly, as this happened

only a matter of weeks before the buyout of Vectorbeam

by Cinematronics, which nobody at Cinematronics had

apparently forseen. "When Cinematronics took over

Vectorbeam they found themselves stuck in Vectorbeams

position," says Skelly. "They had employees, an assembly

line, and nothing to build. So--and here comes the

irony--they were forced to endure the fate they had

intended for their foes: they had to build Barrier."

Meanwhile, while the rival frat house rubs were going

on down in El Cajon, Atari had just unleashed Lunar

Lander, its first vector game, which, like

Cinematronics' first vector, was based on an older

computer game which had been around for a while. It

had an interesting control lever for thrust, and the

display was virtually identical to what players had

seen on the black and white vector monitors of Cinematronics

and Vectorbeam. Lunar Lander's production was stopped

abruptly, however. In fact, so abruptly that cabinet

production was well ahead of the rest of the assembly

line, and when Asteroids machines were

grossly outselling and earning Lunar Landers,

the pre-produced cabinets of Lunar Lander

went out with Asteroids in them. Asteroids

was the biggest vector game ever, and Atari's biggest

coin-operated game ever. If Space War

got vector games' proverbial foot in the door of mainstream

arcades, Asteroids knocked it off the

hinges. Gamers across the nation were entranced by

its bright, pulsing graphics and wonderful gameplay.

Back at Cinematronics, Vectorbeam's factory would

produce only a very small number of Barrier

games. And before its doors were shut forever,

Warrior, the world's first one-on-one fighting

game, would be manufactured and unknowingly start

a family tree which would later blossom in the mid

80's with Karate Champ, and later in

the 90's with the blockbuster japanese import Street

Fighter. As with Barrier, it

would be built under the name 'Vectorbeam a Cinematronics

company' and very few were produced. Warrior

utilized the best video game cabinet artwork ever,

exterior and interior, to make it a wonderous spectical.

Sunday and Rosenthal's Tailgunner would

be given finishing touches by Skelly and released

at Cinematonics to mediocre results. Likewise, Scott

Boden's Solar Quest acheived only modest

production. However, things quickly looked up as Star

Castle began a run of success for Cinematronics

(helped by Asteroids possibly?) selling

well and giving players some color to look at. The

rings in Star Castle were each a different

color, implemented with a multi-colored overlay over

a black and white monitor. Along with being a great

game, and spicing up the display with its overlay,

it was one of (if not the) first video games with

an element of artificial intellegence. A small 'fuseball'

chased the player around, adjusting to the movement

of the player's spaceship, and acting independent

of the rest of the actions in the game.

Rip-Off was next. It's gameplay possessed

another first. It was the first two-player simultaneous

co-operative game. Although games like Space

War and Tank had pitted players

in head-to-head battle, Rip-Off challenged

them to work together, as that was the best way to

protect your fuel canisters from being stolen and

achieve high scores.

The final game by Skelly, and the final black and

white vector game produced by Cinematronics, was Armor

Attack. Controlling your tank in a downtown

war zone, players had to navigate buildings, battle

other tanks, and also deal with attack from the air,

an element unique to this bird's eye viewed tank game.

Helicopters zoomed onto the screen, attempting to

ambush and destory the players tanks. Skelly left

Cinematronics before Armor Attack saw

production. "Why?" you ask. "Where did he go?" you

say. Well, read on...as I ask Tim those very things

in an exclusive interview.

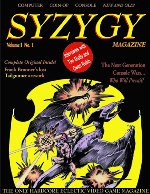

Want to read Part 2 of "The Rise and Fall

of Vectors?"

Get your hungry hands on the first issue of

Syzygy

Magazine